Pipelines and Inroads

The Andy Warhol Museum

Front façade of The Andy Warhol Museum. Photo by Abby Warhola.

The Andy Warhol Museum fits within a simple narrative at first glance—the largest single-artist museum in North America devoted to presenting and circulating globally the most complete collection of Warhol’s work. In fact, Andy Warhol’s legacy lends itself to the plurality of narratives and identities embodied in the museum. For many of the museum’s visitors, the seven-story prewar industrial building has become a place of pilgrimage, a destination to pay homage to one of the most enduring American success stories. While the museum rotates these patrons through thoughtfully crafted pairings of archival material from Warhol’s life with iconic paintings, film, and interactive art, the staff of the museum simultaneously work to manifest the complexity of Warhol’s legacy through a range of local community engagement initiatives and exhibitions of contemporary artists who are in dialogue with his work. Here we encounter an appropriate contradiction—the artist who rejected his place of birth to pursue wealth and fame has, in his death, catalyzed the creation of a space for both newcomers and the marginalized in his home city of Pittsburgh.

As such, we see in The Warhol the case of a museum reflecting on international immigration issues, while operating within the deindustrialized rustbelt in a polarized political setting (a blue city in a red state).[1] We also see a thriving cultural organization embedded in a historically disenfranchised neighborhood, and a legacy of New York counterculture and glamour abutting severe poverty.[2]

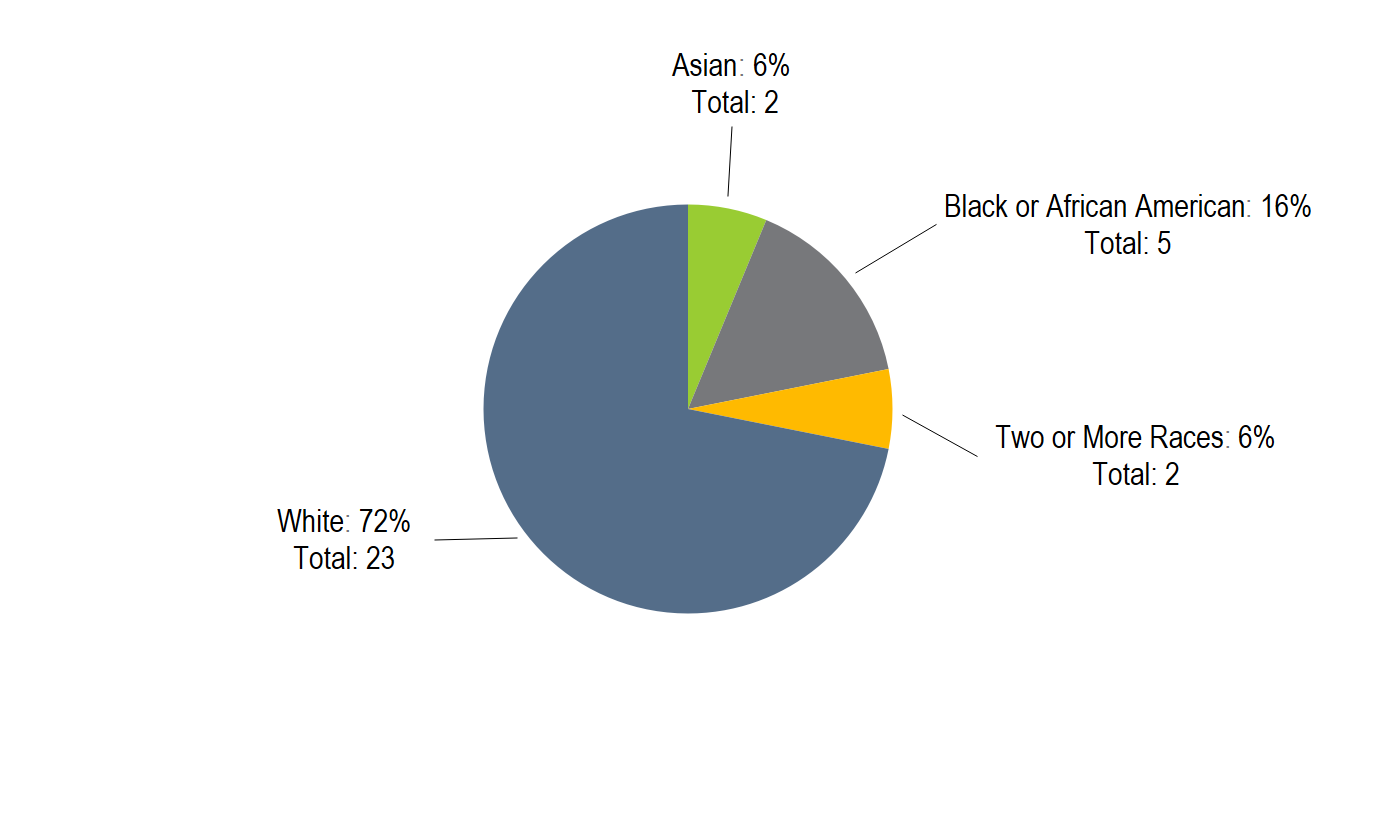

The Andy Warhol Museum stands out in other ways as well. In 2015, Ithaka S+R, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the American Alliance of Museums (AAM), and the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD) set out to quantify with demographic data an issue that has been of increasing concern within and beyond the arts community: the lack of representative diversity in professional museum roles.[3] Specifically, 84 percent of staff holding education, curatorial, conservation, and senior administrative positions across AAMD member museums were white non-Hispanic. The Andy Warhol Museum showed greater racial diversity in these positions, with 12 percentage points more people of color in these positions than the national aggregate.[4]

Figure 1. Racial/Ethnic Composition of The Andy Warhol Museum’s Educators, Curators, Conservators, and Senior Administrators.

What does this say about the rest of the art museum sector if the Warhol, three-quarters white, is an outlier in diversity?

The museum doesn’t consider these numbers to be much of an accomplishment. As director Patrick Moore expressed, what does this say about the rest of the art museum sector if the Warhol, three-quarters white, is an outlier in diversity?

Key Findings

Among the eight museums profiled in the case studies, The Andy Warhol Museum is one of two located in the rust belt. It is the sole single-artist museum, although it also dedicates one floor to exhibitions by contemporary artists influenced by Warhol. In the 2015 Art Museum Demographic Survey, it reported 83 full- and part-time staff.

The three-day site visit involved interviewing 12 people, participating in a convening of neighborhood community organizations, exploring galleries and archives, observing meetings, and participating in educational programs. The visit to The Andy Warhol Museum revealed much about the nature of the museum’s staff diversity, the connection between staff diversity and community outreach, and efforts to highlight social justice issues in programming and expand the diversity of exhibitions. After conducting follow-up interviews and further research, we found three areas of activity that have helped the museum achieve a relatively diverse professional staff and foster an inclusive environment:

- Diversifying the Pipeline: The education department is largely responsible for the diversity at the Warhol. They’ve achieved this through an emergent pipeline strategy that they are now working to formalize.

- Expanding Mission: Though some could view a commitment to Warhol’s legacy narrowly, the museum’s curatorial department has excelled in diversifying programming while remaining true to mission.

- Raising Cultural Awareness: What is the best way to deal with a communications mishap that raises questions of cultural appropriation? By engaging the controversy the museum found a way to strengthen community ties.

Challenges and Tradeoffs

Despite relative success in diversifying its staff, the museum faces two notable challenges that put its accomplishments towards diversity, equity, and inclusion at risk:

- Integration: Without formalizing and integrating pipeline initiatives throughout the museum, efforts toward diversifying staff can remain isolated in a single department.

- Cultural Sensitivity: Embracing a role of provocateur in an institutional context can lead to conflicts over cultural sensitivity.

History and Context

Pittsburgh is famously controversial for punishing labor conditions and violent strikebreaking tactics during its industrial rise in the 19th and 20th centuries.[5] It was central to America’s “arsenal for democracy” during World War II, producing 95 million tons of steel for the war effort. However, between the end of World War I and the early 1980s, Pittsburgh’s share of national steel production fell from 25 percent to 14 percent, leading to the loss of over 100,000 manufacturing jobs as the city plunged into economic crisis.[6] Its population peaked shortly after the war at 676,806, and has since declined to less than half of that, with even fewer residents than the Pittsburgh had prior to its annexation of Allegheny City (North Side) in 1907.

During the 1970s, Pittsburgh began to recognize its cultural offerings as an increasingly meaningful economic asset, with potential to attract tourist dollars and stem the drain on the city’s population.[7] The Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh were perhaps the crown jewel of these offerings, with the Carnegie International, a survey of contemporary art recurring every three to five years, rising to a prominent position in the art community. Alongside the Carnegie Institute, the city established a cultural trust, making meaningful investments in a downtown cultural district in 1971. In a significant addition to these assets, the city worked with the Carnegie Institute, the Andy Warhol Foundation, and the Dia Foundation to establish The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh’s North Side, after the artist’s death.

Pittsburgh’s North Side, known as Allegheny City prior to the controversial annexation in 1907, has a storied history that reflects the extreme class disparities that have become central to public discourse in the twenty-first century. Located on the north shore of the Allegheny River, it connects to Pittsburgh’s downtown through a series of bridges. Prior to the Great Depression it was home to an immense concentration of wealth. Though the residential areas have suffered setbacks since annexation, parts of the North Side have prospered, and a stretch along the riverbank has been developed into an attractive entertainment district. Popular destinations include the baseball stadium PNC Park, the football stadium Heinz Field, the concert venue Stage AE, The Andy Warhol Museum, the Carnegie Science Center, and the Rivers Casino. While tourists are likely to find themselves at the North Side, they are unlikely to cross Interstate 279 into the more-residential areas, where roughly one-fourth of the population lives below the poverty line—more than twice the rate of the wider Pittsburgh metro area.[8] Thirty-six percent of North Side residents are African American—ten percentage points higher than the city of Pittsburgh as whole. The urban-design barriers (most prominently, the interstate) pose a challenge for many of the cultural organizations in the North Side that are located closer to the Allegheny River shore. They are cut off from their local public.

Two elements contributed to the existence of the Andy Warhol Museum—the artist’s unprecedented fame and his penchant for hoarding. While enough of his archival material objects are stored at the museum that they are unlikely to be fully cataloged by the museum’s two assiduous archivists (and their successors) until the late twenty-first century, many of his collected objects were sold at auction at the time of his death to endow and establish the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts.[9] This foundation decided to establish a museum to house his works and keep them available to the public. For financial reasons and considerations of institutional impact, Pittsburgh was named home to the museum.[10] Planners identified a prewar industrial building in the North Side, evocative of Warhol’s iconic 1960s studio. The museum was established at this site in 1994. Since then, Pittsburgh has enjoyed a revitalization, ranking in a 2014 report issued by the Economist Intelligence Unit as the most livable city in the continental United States.[11]

Although Pittsburgh is home to an uncommonly high degree of philanthropy for a midsize city, The Andy Warhol Museum finances itself primarily through traveling exhibitions.[12] In this aspect, Patrick Moore, who assumed directorship of the museum after Eric Shiner stepped down in 2016, described it as one of the most entrepreneurial museums in the country. This financial model has its benefits, including promoting material stability during economic downturns such as the 2008 financial crisis; by maintaining its own revenue stream, the museum makes itself less vulnerable to fluctuations in philanthropy and financial markets. However, the model also presents challenges: for example, the museum is cognizant that it will have to decrease the amount of international travel in order to maintain the integrity of the art.

“If credentials are broadened then it’s less hierarchical, and it becomes easier to achieve diversity.”

According to Moore, this entrepreneurial spirit, which he sees as connected to Warhol’s commercial legacy as much as it is borne out of necessity, also attracts a different type of employee. Indeed, Moore fits that description, having assumed the directorship in 2016 after moving from the position of director of development to deputy director and then managing director before assuming his current role. He thinks that job descriptions in the cultural sector have been drawn too narrowly, and that this in part accounts for the lack of diversity in the field; in his words, “if credentials are broadened then it’s less hierarchical, and it becomes easier to achieve diversity.” This openness has generated a culture at the Warhol that is welcoming, a haven for communities historically excluded from many cultural institutions.

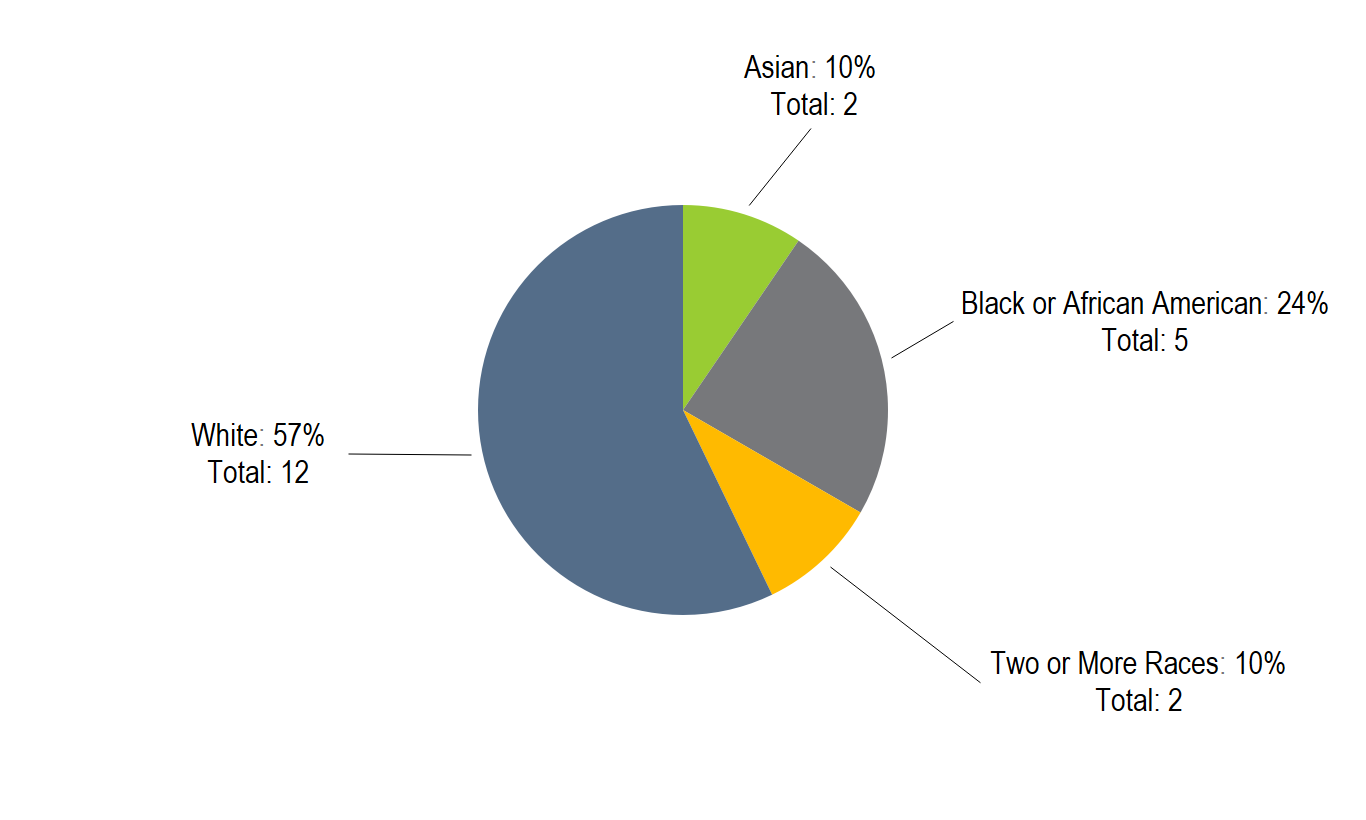

Diversifying the Pipeline

A deeper investigation of the racial/ethnic composition of The Andy Warhol Museum showed that diversity in the professional positions was consolidated in the education department until 2016. In fact, in 2015, all curators, conservators, and senior administrators were white non-Hispanic. Nine staff members in the education department, however, were people of color. At 43 percent, this is above the average for the city. It was quickly revealed that this was no accident. Led by Danielle Linzer, director of learning and public engagement, the education department has been deeply engaged in pipeline development for years—a practice which is now informing the museum as a whole.[13]

Figure 2: Racial/Ethnic Composition of The Andy Warhol Museum’s Educators.[14]

In her previous position at the Whitney Museum of American Art as director of access and community programs, Linzer led a collaborative research project to better understand the impact of youth programming in museums. Funded by a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS), the study involved a collaboration between the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Contemporary Arts Museum of Houston, the Walker Art Center, and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. The resulting publication, Room to Rise, revealed the lasting benefits of museum programs for teens—one of the first studies to measure the impact of these youth programs.[15] In many ways, the research reinforced Linzer’s commitments to her work cultivating relationships between museums and youth; over half of the participants in Room to Rise described their involvement with the museum as one of the most important experiences of their lives. Drawn to The Warhol because of their strong track record of proactive youth development, she has applied this research in her current role, creating multiple points of access to the museum for marginalized communities in Pittsburgh.

Linzer sees the unofficial pipeline program that has diversified the education department as a result of their youth programming initiatives. She told us that the isolated diversity in education “is a direct product of these initiatives. The education department has always made it a priority to hire diverse people. Right now, several educators of color came up through our programs and have moved through to different long-term opportunities. Articulating these pathways of inclusion are now goals for the larger organization and not just the education department.”

Culturally Specific Programs

Over the years the museum has offered culturally specific programs such as Power Up, an off-site art program for young African American women, and Swishy, a publication by and for queer teens. The museum also serves as an invaluable asset for the LGBTQ+ community regionally, including through hosting events such as the the annual LGBTQ+ Youth Prom, which draws attendance not only from Pittsburgh, but also from the surrounding western Pennsylvania counties. As research has shown, the experience of queer identity in Appalachia can be alienating.[16] One attendee who lives an hour and a half outside of the city described the museum as a respite from those in their hometown who often levy accusations that their “gender is fake.” Another attendee of the prom explained that without The Warhol, queer communities in the region would be mainly limited to digital platforms. But it is essential for people to come together in person. In serving this function, a young audience is introduced to the cultural offerings of the institution.

Culturally specific programs, along with a suite of additional off- and on-site educational offerings and partnerships, serve as a point of entry into the museum world. The education department has designed a pathway for further engagement for those whose interest is piqued. For instance, the Youth Arts Council gives young people the opportunity to go behind the scenes at the museum to develop events and experiences for other young people. Fifteen students a year are provided a stipend and gain work experience that can open their eyes to the possibilities of careers in the arts. Because the access points for this program are often derived from the museum’s various outreach programs, the department is able to be deliberate about practices of inclusion as it develops each cohort.

Often internship opportunities result for students who are interested in further engagement. The museum participates in various citywide initiatives to offer paid internships for youth, and is now introducing more paid apprenticeship opportunities internally. Student assistants work in the museum supporting education programs as well as off-site with partners. “At this point, they are essentially part of the staff of the museum, apprenticing to be artist educators,” Linzer said. “The Warhol does not have a docent program, and all education programs are delivered by artist educators. I think this is also a key contributing factor for diversity.” Instead of security staff, the museum has gallery attendants, who safeguard the work and act as liaisons with curatorial and education departments. They are often hired out of this same cohort, and the job is another important point of entry into the museum and a career in the arts.

Quaishawn Whitlock, a Pittsburgh local, progressed through this pipeline beginning in high school. He now works as an artist educator in the museum. Through the Fund for Advancement of Minorities through Education (FAME), he received a paid internship at The Andy Warhol Museum in “The Factory”—a studio space in the basement of the museum—facilitating silkscreen printing activities and other education programs for the public. After high school he moved to Eastern Pennsylvania to attend a prestigious engineering college. He described the awkwardness of being tokenized as an African American there, while also witnessing acts of discrimination. He brought his concerns to the senior administration of the school, who responded only by saying that they were grateful to have a student on campus who was so attuned to these issues. He left the university and returned to Pittsburgh, where he finished his degree and began working at The Andy Warhol Museum in education. He now offers on-site workshops at Perry High School—a public school in the North Side where over 85 percent of the student body receives free or reduced lunch—and helps run the museum’s youth development and artmaking programs for teens. He is working to create similar opportunities for youth in the neighborhood.

Moore described how outreach efforts in the education department relate to the museum’s finances from a development perspective, saying, “We’re one block away from Pirates and Steelers. We’re a city of sports fanatics. Anybody trying to raise money here has to explain why they are relevant, why they matter. And we can’t just say ‘Warhol.’ We have to say we’re important because we’re going to help your kids learn how to get a job.” As Moore describes it, the museum’s development efforts align with, even rely on, the inroads museum educators create in the community.

The pipeline has, up to this point, been operating informally. Linzer is working now to integrate these efforts into the broader museum culture and support partnerships between the education and curatorial departments. Toward this end, The Warhol recently received a grant from the Ford Foundation and Walton Foundation “for a multi-tiered pipeline project including a youth outreach program, internships, and alumni and mentoring programs.” This grant will allow the museum to formalize many of the efforts that have grown through the commitments of the museum staff.[17] Linzer likes to think of these efforts as naturally extending from Warhol’s legacy: “Andy Warhol was a sickly, poor, openly gay immigrant, raised in depression-era Pittsburgh, the first to attend college in his family. It’s not specious for us as an institution to think hard about engaging those who aren’t traditional audiences or to think about pathways for staff who aren’t traditional. It’s an extension of our mission.”[18]

“It’s not specious for us as an institution to think hard about engaging those who aren’t traditional audiences or to think about pathways for staff who aren’t traditional. It’s an extension of our mission.”

These pipeline initiatives have taken some time to spread to other parts of the museum. While there was no racial diversity in the curatorial department in 2015, that has changed in the last two years. As of the site visit, the department includes three people of color and is headed by chief curator José Diaz.[19] Diaz and his colleague Jessica Beck were recently promoted through a staff reorganization—one of the first changes for Moore as director. As Moore described it, “Because I’m not a curator, I thought it was important for curatorial to be represented on the senior management team. I wanted José to become our senior curator because although he is an excellent curator he also has management skills.” Moore sees potential for Diaz to lead a museum one day, and is working to prepare him for that moment.

Expanding Mission

The Andy Warhol Museum is exemplary among its peers in placing accessibility issues at the center of its institutional mission. As the “global keeper of Andy Warhol’s legacy,”[20] Moore sees it as a challenge and an imperative for the museum to improve the visitor experience for the disabled, even if manifesting this mission would not necessarily yield deliberate efforts toward access and inclusion for every leader. In recent years, The Warhol has introduced sensory-friendly events, universally designed exhibitions featuring tactile reproductions of signature artworks, an award-winning inclusive audio guide,[21] and an accessible website.[22]

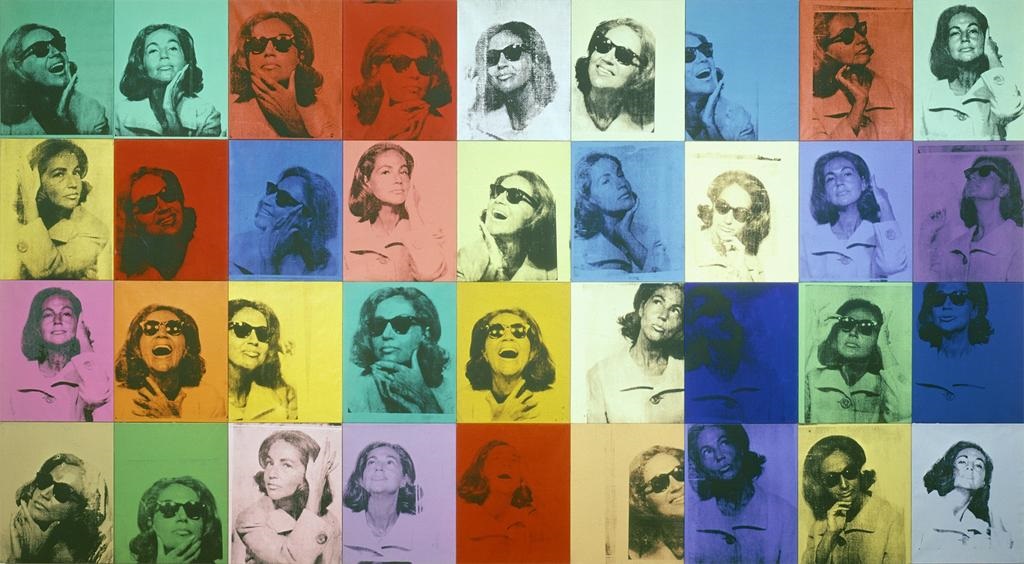

The Andy Warhol Museum also thinks about diversity and inclusion in its curatorial practice. Recently named chief curator, Diaz brings an international curatorial sensibility to the museum, having worked formerly at Tate Liverpool and the Bass Museum. Unlike some other single-artist museums where legal stipulations restrict the building to house solely the namesake artist’s works, The Andy Warhol Museum maintains a gallery for rotating contemporary exhibitions. The exhibitions must be in dialogue with Warhol’s work in a way that expands the meaning of both, a requirement that would be much more limiting for a less influential artist. In a recent exhibition, Firelei Báez’s work was on display. Senior curator Jessica Beck first recognized that Báez’s art connected to themes in Warhol’s when she first saw Bloodlines on display at the Pérez Art Museum Miami. While on the surface Báez’s paintings—which blend Dominican folklore, social resistance, and intimate reversals of gaze—seem largely independent of Warhol’s legacy, Beck saw meaningful connections.[23]

One of the most apparent of these connections is in a work of serial portraits. Báez said she wasn’t explicitly thinking of Warhol when she made the painting, but it is clearly evocative of Warhol’s Ethel Scull Thirty-Six Times (1963). Báez felt she had inherited the tradition of Byron Kim and Lorna Simpson. “But Warhol had to be central to their way of thinking of what art is and how it can function, this idea of nuance through repetition. I inherited their tradition, they inherited Warhol.” In these silhouettes, configured as a calendar grid, Báez paints her hair, head, and shoulders the color of her skin tone on each given day in the month of June. The piece, Can I Pass? Introducing the Paper Bag to the Fan Test for the Month of June (2011), refers to one “test” used in the Caribbean community to determine whiteness versus blackness—whether or not one’s skin was darker than a brown paper bag. As Báez said, “The brown paper bag is such a banal object, something you throw away. But to not be able to marry someone, to have it be a standard of beauty within the community, it’s kind of intense. Colorism in Latin America functions as the opposite of the US. In Latin America one drop does make you closer to whiteness. Whereas in the U.S. any drop of black makes you absolutely black, it’s this tainting.”

Andy Warhol, Ethel Scull Thirty-Six Times (1963)[24]

Firelei Báez, Can I pass? Introducing the Paper Bag to the Fan Test for the Month of June (2011)

Also on display in Bloodlines were paintings of elaborate tignons[25] with revolutionary symbols and Ciguapas from Dominican folklore, as well as abstractions related to the craft of developing these images.[26] Bloodlines is housed in a gallery designed after the Sans-Souci Palace in northern Haiti, which Báez says is a pivotal space for black revolutionary identity.[27] A team of volunteers assisted the artist in constructing the space; when the exhibition came down in May, the volunteers each took a piece home with them.

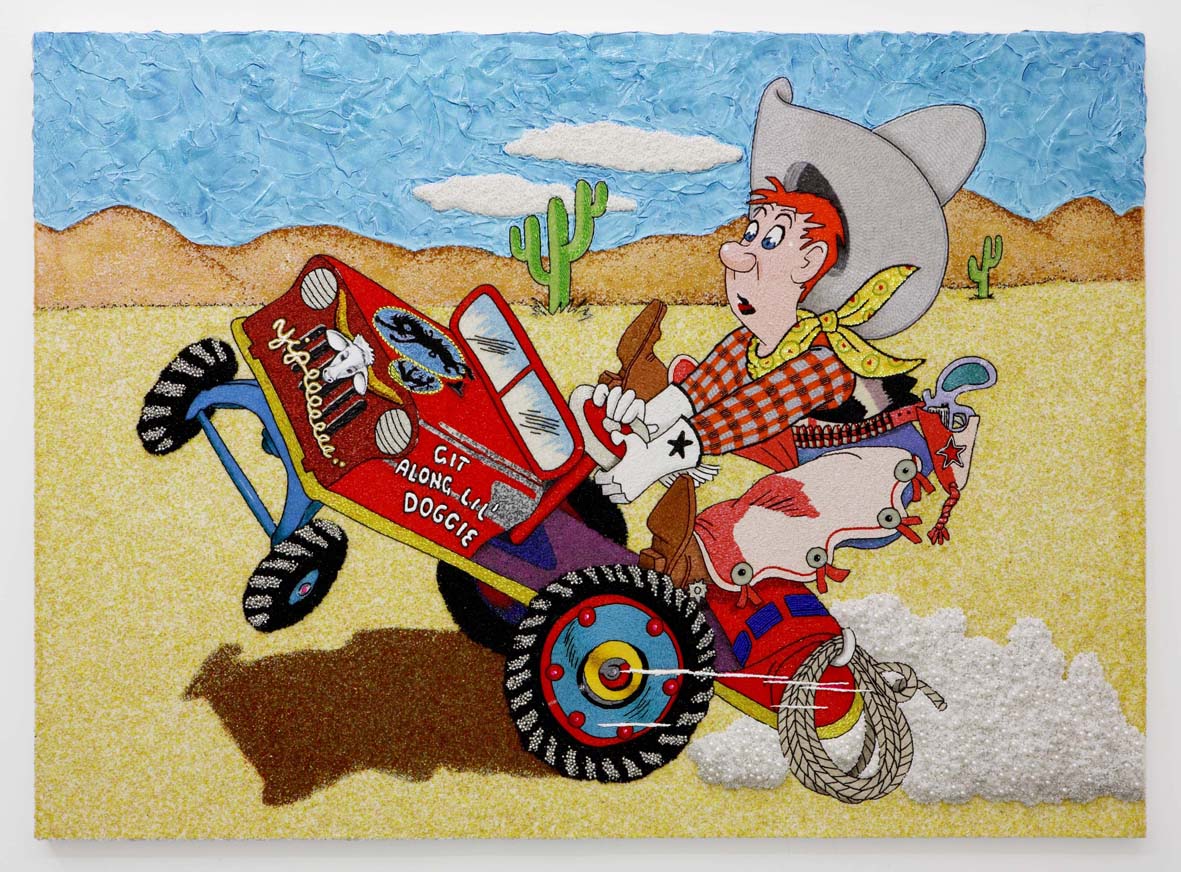

Following the Báez exhibition, Diaz brought the first solo museum exhibition of Iranian artist Farhad Moshiri to The Warhol. Moshiri’s work offers a fascinating insight into American kitsch from an Iranian perspective, addressing “contemporary Iran’s traditions and historic isolationism, and simultaneously acknowledging the powerful appeal and influence of Western culture in his homeland.” Diaz explained that the significance of the exhibition changed in light of the travel ban, as logistics grew more complicated. The travel ban adds a degree of irony to the exhibition, which reflects imported American pop and kitsch images through an Iranian cultural lens.

Farhad Moshiri, Yipeeee (2009), hand-embroidered beads and acrylic on canvas. Photo by The Andy Warhol Museum

The curatorial vision that connected this exhibition to The Andy Warhol Museum illustrates the power of maintaining an expansive view of the museum’s mission. Under different leadership, or with a different culture, the museum might have pursued a more obvious course—perhaps focusing on Warhol’s contemporaries, approaching the exhibition space with an eye toward nostalgia. But The Warhol’s curatorial interests lead instead toward exhibitions that confront the complexities of America’s international identity, and that foreground underrepresented cultural narratives in relation to Warhol’s legacy.

Raising Cultural Sensitivity

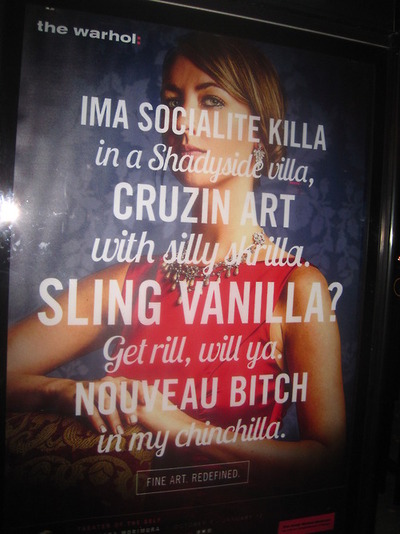

The Warhol museum has, in some cases, struggled to find the line between provocation and appropriation. Between 2013 and 2014 the Warhol Museum held an exhibition of Yasumasa Morimura’s work called Theater of the Self, which featured Morimura’s face superimposed on famous portraits. The museum’s ad agency produced a campaign for the exhibition that overlaid its own Pittsburgh-specific rap lyrics on images of wealthy white people.

Image from “Fine Art. Redefined” ad campaign (2014)[28]

The ad campaign, called “Fine Art. Redefined,” ran in print ads throughout Pittsburgh. Both the director of communications, Rick Armstrong, and former director Eric Shiner expressed that The Andy Warhol Museum, true to form, often acts as a provocateur. In this case, they expected to field phone calls from Pittsburgh’s old money, the community they intended to poke fun at. However, local African American artist and activist D. S. Kinsel, along with three collaborators, wrote to the museum criticizing them for cultural appropriation: “This culture jacking of sorts is a reckless disregard for how Hip-Hop culture could and should be viewed in its entirety! These ads are a great example of how cultural appropriation fails to benefit society as a whole.” The letter offered a suggestion: “Morimura referred to his work as a, ‘beautiful commotion’ and although provocative these ads should be followed by art, discussion, and programming that actually address the very issues these ads exemplify.”

Shiner and Kinsel arranged to sit down and discuss these concerns. Kinsel said, “Shiner apologized and came with respect. We were able to share our narratives. That’s how things get misconstrued.” Out of this conversation grew an artist residency called Activist Print, which the Warhol helped to establish through Art Basel’s crowdfunding initiative.[29] This multi-year program started with a mural project addressing police brutality, which used bullet points from the Obama administration’s 21st Century Policing report.[30] The murals are installed in vacant properties, turning them into spaces for public art. Kinsel’s mural, What They Say, What They Said (2016), sparked a dialogue with the former chief of police in Pittsburgh, Cameron McLay, which led to a coordination of a symposium with the chief of police, police commander, and D. S. Kinsel, moderated by Eric Shiner. Kinsel and Shiner both felt the forum was a positive step toward improving relations between the two groups.

D. S. Kinsel with Public Mural, What They Say, What They Said. Photo provided by Boom Concepts

Shiner said he and the staff were mortified when they realized the ad campaign for the Morimura exhibit offended one of their community partners. But instead of shying away from the controversy, they dug into the conversation and collaborated in a way that ultimately created inroads between two polarized groups. In this way, the museum became an integral civic space for discourse between communities.

Conclusion

Over the course of the site visit, a common refrain emerged as interviewees considered how to describe the organization. “The Warhol tries,” was repeated across junior and senior positions. There are a number of specific meanings embedded in the phrase. The Warhol tries to consider diversity while hiring, and has done explicit pipeline work to make that happen. They try to think expansively in their curatorial practice, to include work that might not traditionally fall into the milieu of 1960s Pop Art. They try to address their mistakes, using them as opportunities to listen, build relationships, and facilitate conversations.

This message came most resoundingly from an external interview with president of the Buhl Foundation, Diana Bucco. The Buhl Foundation conducts research and targeted philanthropy in the North Side to address the most persistent issues facing the underserved in those neighborhoods. She said of The Andy Warhol Museum, “They have chosen to make community engagement a core value and a priority. Not everyone has done that. Others just say, ‘Well, we had our community day and no one came.’”

Through building a presence in underserved communities and providing opportunities for youth to advance within the education department, the museum has grown significantly more diverse than the regional and national cultural sector.

The Andy Warhol Museum’s approach can be adapted, especially for institutions who are not located in a highly diverse metropolis, or whose mission does not explicitly call for prioritizing inclusion, diversity, and equity. Through building a presence in underserved communities and providing opportunities for youth to advance within the education department, the museum has grown significantly more diverse than the regional and national cultural sector. The administration has worked to think inclusively in its curatorial practice, creating a space in the museum where the visitors can engage with non-Western heritage and see connections to iconic American images. A moment of friction with an underrepresented community became the genesis of an ongoing artist residency program that creates yet more inroads to the museum. As the global keeper of Andy Warhol’s legacy, the museum sees commitments to inclusion, diversity, and equity as an imperative.

Appendix

Case Studies in Inclusion, Diversity, and Equity among AAMD Member Art Museums

Three years ago, Ithaka S+R, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD), and the American Alliance of Museums (AAM) set out to quantify with demographic data an issue that has been of increasing concern within and beyond the arts community: the lack of representative diversity in professional museum roles. Our analysis found there were structural barriers to entry in these positions for people of color. After collecting demographic data from 77 percent of AAMD member museums and an additional cohort of AAM art museums that are not members of AAMD, we published a report sharing the aggregate findings with the public. In her foreword to the report, Mariët Westermann, executive vice president for programs and research at the Mellon Foundation, noted, “Non-Hispanic white staff continue to dominate the job categories most closely associated with the intellectual and educational mission of museums, including those of curators, conservators, educators, and leadership.”[31] While museum staff overall were 71 percent white non-Hispanic, we found that many staff of color were employed in security and facilities positions across the sector. In contrast, 84 percent of the intellectual leadership positions were held by white non-Hispanic staff. Westermann observed that “these proportions do not come close to representing the diversity of the American population.”

The survey provided a baseline of data from which change can be measured over time. It has also provoked further investigation into the challenges of demographic representation in this sector. Many institutional leaders are growing increasingly aware of demographic trends showing that in roughly a quarter century, white non-Hispanics will no longer be the majority in the United States, whereas ten years ago the white non-Hispanic population was double that of people of color.[32] This rapid growth indicates that cultural institutions such as museums will need to be intentional and strategic in order to be inclusive and serve the entire American public.

To aid these efforts, AAMD, the Mellon Foundation, and Ithaka S+R partnered again to launch a new effort to understand the following: What practices are effective in making the American art museum more inclusive? By what measures? How have museums been successful in diversifying their professional staff? What do leaders on issues of social justice, equity, and inclusion in the art museum have to share with their peers?

Using the data from the 2015 survey, we identified 20 museums where underrepresented racial/ethnic minorities have a relatively substantial presence in the following positions: educators, curators, conservators, and museum leadership. We then gauged the interest of these 20 museums in participating, also asking a few questions about their history with diversity. In shaping the final list of participants, we also sought to ensure some amount of breadth in terms of location, museum size, and museum type. Our final group includes the following museums:

- The Andy Warhol Museum (Pittsburgh)

- Brooklyn Museum

- Contemporary Arts Museum Houston

- Detroit Institute of Arts

- Los Angeles County Museum of Art

- Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago

- Spelman College Museum (Atlanta)

- Studio Museum in Harlem.[33]

In shaping the final list of museums to profile, we also sought to ensure some amount of breadth in terms of location, size, and type.

We then conducted site visits to the various museums, interviewing between ten and fifteen staff members across departments, including the director. In some cases, we also interviewed board members, artists, and external partners. We observed meetings, attended public events, and conducted outside research.

In the case studies in the series, we have endeavored to maintain an inclusive approach when reporting findings. For this reason, we sought the perspectives of individual employees across various levels of seniority in the museum. When relevant we have addressed issues of geography, history, and architecture to elucidate the museum’s role in its environment. In this way the museum emerges as a collection of people—staff, artists, donors, public. This research framework positions the institution as a series of relationships between these various constituencies.

We hope that by providing insight into the operations, strategies, and climates of these museums, the case studies will help leaders in the field approach inclusion, diversity, and equity issues with a fresh perspective.

Endnotes

- William A. Galston, “Why Hillary Clinton lost Pennsylvania: The Real Story,” Brookings Institution, November 11, 2016, accessed July 20, 2017, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/fixgov/2016/11/11/why-hillary-clinton-lost-pennsylvania-the-real-story/. ↑

- Dan Rooney and Carol Peterson, Allegheny City: A History of Pittsburgh’s North Side (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2014). ↑

- Please see the appendix at the end of this paper for a fuller description of the survey, methodology, and how we selected museums to include in this case study series. ↑

- This project benefitted greatly from the contributions of the advisory committee. Our thanks to Johnnetta Betsch Cole, Senior Consulting Fellow at the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation; Brian Ferriso, Director of Portland Art Museum; Jeff Fleming, Director of Des Moines Art Center; Lori Fogarty, Director of Oakland Museum of California; Alison Gilchrest, Program Officer, The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation; Susan Taylor, Director of New Orleans Museum of Art; and Mariët Westermann, Executive Vice President, The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.We would also like to thank Christine Anagnos, Executive Director AAMD, and Alison Wade, Chief Administrator AAMD, for their organizational support in this project.And we are grateful to Patrick Moore, Director of the Andy Warhol Museum for his willingness to participate in the study, and Danielle Linzer, Director of Learning and Public Engagement, for her many contributions to the project. ↑

- Arthur G. Burgoyne and David P. Demarest, The Homestead Strike of 1892 (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1979); Herrick Chapman, “Pittsburgh and Europe’s Metallurgical Cities: A Comparison,” in City at the Point: Essays on the Social History of Pittsburgh, ed. Samuel P. Hays (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1989), 407–36, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt7zw8rx.18. ↑

- Laurence Glasco, “Double Burden: The Black Experience in Pittsburgh,” City at the Point, 69–110, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt7zw8rx.7. ↑

- Roy Lubove, “Amenities and Economic Development,” in Twentieth-Century Pittsburgh, Volume Two: The Post-Steel Era (London and Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1996), 185–207, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt9qh7b5.13. ↑

- Carol J. De Vita and Maura R. Farrell, “Poverty and Income Insecurity in the Pittsburgh Metropolitan Area,” accessed October 24, 2017, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/33571/2000009-Poverty-and-Income-Insecurity-in-the-Pittsburgh-Metropolitan-Area.pdf. ↑

- Christopher Schmidt. “Warhol’s Problem Project: The Time Capsules,” Postmodern Culture 26, no. 1 (2015); see also Gary Rotstein, “Census data show improved poverty rate in Pennsylvania,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, September 17, 2015, accessed October 20, 2017, http://www.post-gazette.com/news/state/2015/09/17/Census-data-show-improved-poverty-rate-in-Pennsylvania/stories/201509170075. ↑

- Grace Glueck, “A Little Late, Warhol Goes Home to Pittsburgh,” New York Times, April 30, 1994, accessed July 28, 2017, http://www.nytimes.com/1994/05/01/arts/art-a-little-late-warhol-goes-home-to-pittsburgh.html?pagewanted=all. ↑

- Economist Intelligence Unit, “A Summary of the Livability Ranking and Overview August 2015,” accessed October 24, 2017, http://www.vancouvereconomic.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/EIU-Liveability-Ranking-Aug-2015.pdf; “Pittsburgh gains another top accolade,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, accessed October 24, 2017, http://www.post-gazette.com/local/region/2014/08/26/City-gains-another-top-accolade/stories/201408260075. ↑

- “Top foundations,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, accessed July 24, 2017, http://www.post-gazette.com/business/In-The-Lead-Companies/2013/05/03/Top-foundations/stories/201305030304. ↑

- Linzer, hired in 2016, was preceded by Tresa Varner, who worked in the education department at the Warhol for twenty years and is now the managing director of Artist Image Resource. ↑

- Though data was not available, the museum also serves as an important resource for the LGBTQ+ community, both in terms of inclusive hiring and outreach/programming. ↑

- Danielle Linzer and Mary Ellen Munley, “Room to Rise: The Lasting Impact of Intensive Teen Programs in Art Museums,” Whitney Museum of American Art, 2015, http://whitney.org/Education/Teens/RoomToRise. ↑

- Kate Black and Marc A. Rhorer, “Out in the Mountains: Exploring Lesbian and Gay Lives,” Journal of the Appalachian Studies Association 7 (1995): 18–28, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41445676. ↑

- Ford Foundation, “Ford Foundation and Walton Family Foundation Launch $6 Million Effort to Diversify Art Museum Leadership,” PR Newswire, November 28, 2017, accessed December 18, 2017, https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/ford-foundation-and-walton-family-foundation-launch-6-million-effort-to-diversify-art-museum-leadership-300562243.html. ↑

- The museum’s mission statement reads: “The Andy Warhol Museum is the global keeper of Andy Warhol’s legacy.” ↑

- These staff identify as Hispanic/Latinx, African American, and Asian American (including summer internship/fellowship positions). ↑

- “Home,” The Andy Warhol Museum, accessed January 08, 2018, https://www.warhol.org/. ↑

- Ian Thomas, “Pittsburgh’s Andy Warhol Museum hosts a sensory-friendly disco for autistic individuals,” Pittsburgh City Paper, October 23, 2017, accessed October 24, 2017, https://www.pghcitypaper.com/pittsburgh/pittsburghs-andy-warhol-museum-hosts-a-sensory-friendly-disco-for-autistic-individuals/Content?oid=2584133. ↑

- Julie Hannon, “Art as an Equalizer,” Carnegie Magazine, Winter 2016, accessed October 24, 2017, http://www.carnegiemuseums.org/cmp/cmag/feature.php?id=610. ↑

- Firelei Báez, Naima J. Keith, and Roxane Gay, Bloodlines, 2015, Pérez Art Museum Miami. ↑

- © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. ↑

- The tignon, a headdress creole women of African descent were forced to wear beginning in the eighteenth century, was intended as a form of sexual control, but was often styled as an attractive accessory, subverting the garment’s colonial intention. See Rebecca Villalpando, “Portrait of a Woman: A Study of The Social Implications of Antebellum Portraiture in New Orleans,” From Slave Mothers and Southern Belles to Radical Reformers and Lost Cause Ladies, accessed July 28, 2017, http://civilwarwomen.wp.tulane.edu/essays-4/portrait-of-a-woman-a-study-of-the-social-implications-of-antebellum-portraiture-in-new-orleans/. ↑

- Ciguapas are often described as tricksters in Dominican folklore, with backward facing feet that mislead those who try to follow them. See Ginetta Candelario, “La Ciguapa Y El Ciguapeo: Dominican Myth, Metaphor, and Method,” Small Axe 20, no. 3 (2016): 100–12. ↑

- Gerald Sider and Gavin Smith, eds, Between History and Histories: The Making of Silences and Commemorations (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1997), http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3138/9781442671324.↑

- D. S. Kinsel, “Sprezzeeland,” #SprezzeeLAND, January 28, 2014, accessed January 08, 2018, http://sprezzeeland.tumblr.com/post/74881661981/a-response-to-the-claim-of-being-fine-art. ↑

- Julie Hannon, “Artistic License: Making Some Noise,” Carnegie Magazine, fall 2016, accessed July 25, 2017, http://www.carnegiemuseums.org/cmp/cmag/article.php?id=581. ↑

- President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing, “Final Report of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing” (Washington, DC: Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, 2015), https://ric-zai-inc.com/Publications/cops-p341-pub.pdf. ↑

- Roger Schonfeld, Mariët Westermann, and Liam Sweeney, “Art Museum Staff Demographic Survey,” Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, July 29, 2015, https://mellon.org/media/filer_public/ba/99/ba99e53a-48d5-4038-80e1-66f9ba1c020e/awmf_museum_diversity_report_aamd_7-28-15.pdf. ↑

- William H. Frey, “A Pivotal Period for Race in America,” In Diversity Explosion: How New Racial Demographics Are Remaking America (Washington DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2015), 1–20, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7864/j.ctt6wpc40.4. ↑

- We focused on people of color for measuring diversity for two reasons: (1) In the 2015 art museum demographic study, we received substantive data for the race/ethnicity variable, unlike other measures such as LGBTQ+ and disability status, which are not typically captured by human resources, and (2) in the study we found ethnic and racial identification to be the variable for which the degree of homogeneity was related to the “intellectual leadership” aspect of the position (i.e., curator, conservator, educator, director). We are alert to issues of accessibility in this project, and although it was not foregrounded in our original project plan we hope to address these questions in more depth in future projects. ↑

Attribution/NonCommercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of the license, please see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.