An Engine for Diversity

Studio Museum in Harlem

The Studio Museum in Harlem is a contemporary, culturally specific, artist-centric museum located in New York City that has played a singular role in defining and promoting the art of African Americans and the African diaspora. The museum has contributed substantially in bringing this art into the canon and equally in providing opportunities for African Americans to gain access to the cultural sector, especially for artists and curators. Through its collections, program, and employees, the Studio Museum’s impact has come to extend well beyond its own walls to diversify the canon and museum staff across the country.

In 2015, Ithaka S+R, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the American Alliance of Museums (AAM), and the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD) set out to quantify with demographic data an issue that has been an increasing concern within and beyond the arts community: the lack of representative diversity in professional museum roles.[1] Through the survey we found that across these organizations, 72 percent of museum staff were white non-Hispanic.[2] In the intellectual leadership positions—identified as educators, curators, conservators, and senior administrators—84 percent of staff were white non-Hispanic. Most of the racial/ethnic diversity within museums existed in facilities and security positions, indicating that aggregate statistics mask substantial differences across job types.

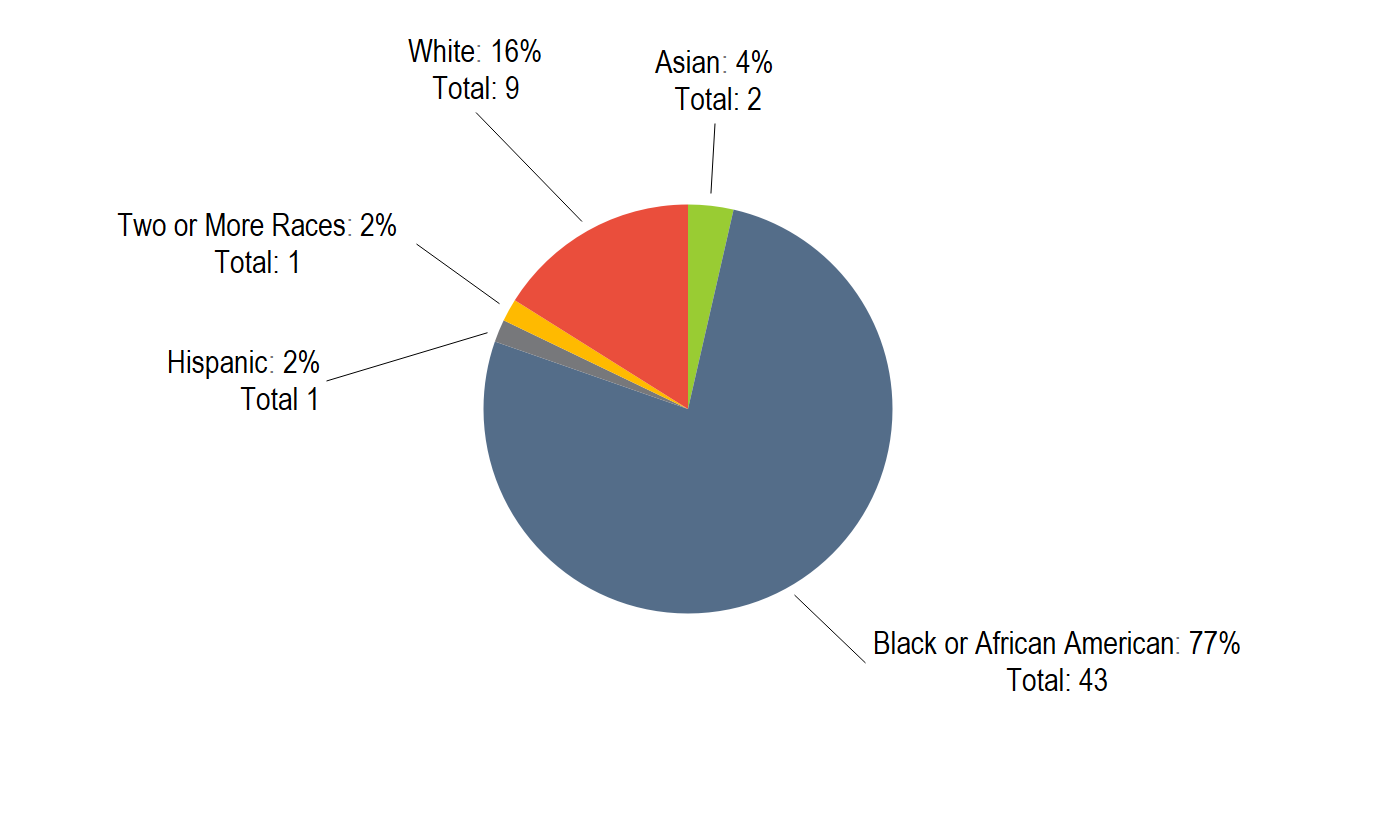

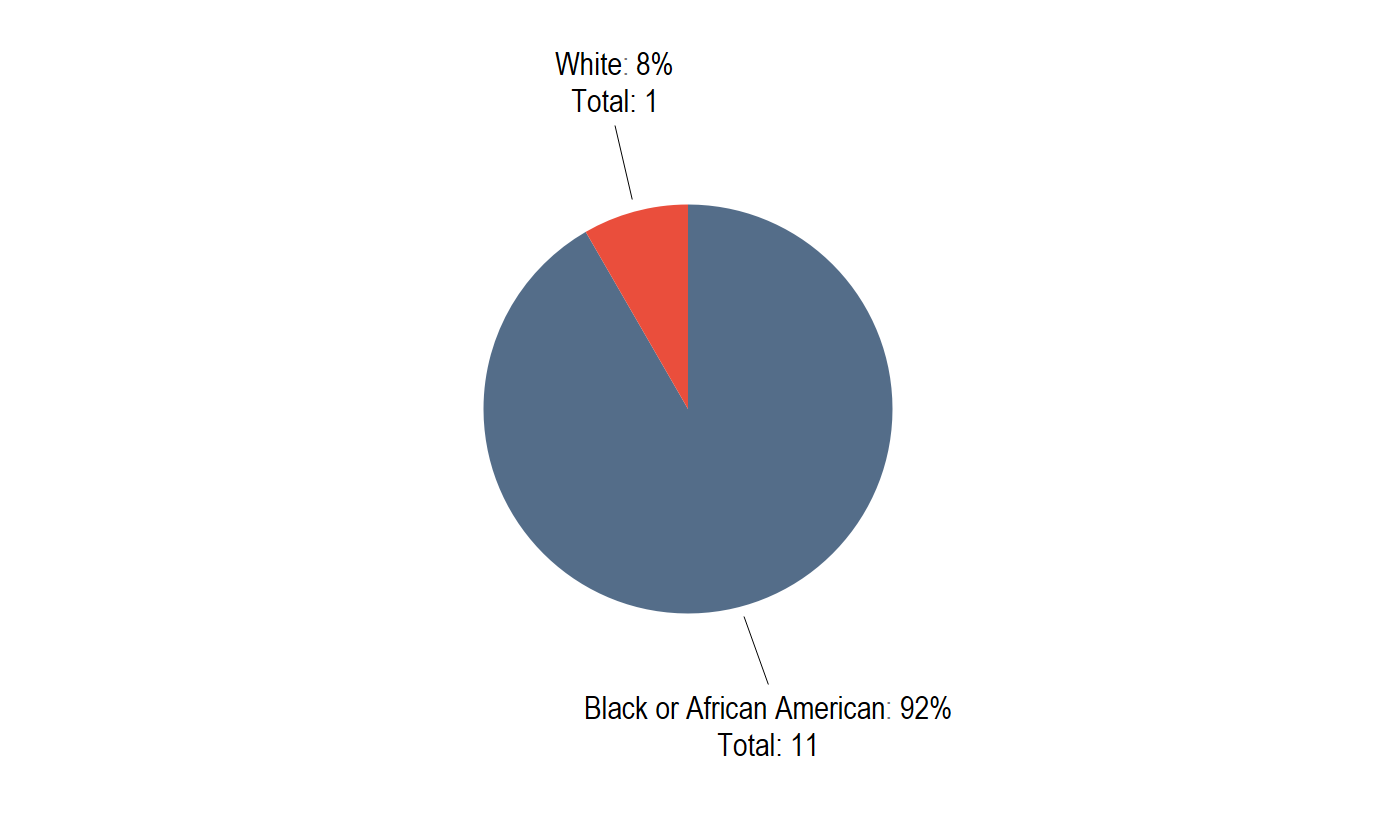

These numbers, however, look very different within culturally-specific museums such as the Studio Museum.[3] As can be seen in Figure 1, 77 percent of the 56 employees at the Studio Museum were black or African American in 2015. Ninety-two percent of the intellectual leadership positions were held by black or African American employees, as can be seen in Figure 2.

Figure 1: Studio Museum in Harlem—All Staff

Figure 2: Studio Museum in Harlem—Curators, Conservators, Educators, Senior Administration

Figure 2: Studio Museum in Harlem—Curators, Conservators, Educators, Senior Administration

Against this backdrop, this case study explores what diversity means for an organization that stands in stark contrast to its majority white counterparts. The Studio Museum has pursued several strategies to create an inclusive organization that is committed to diversifying the larger art community

Key Findings

The Studio Museum in Harlem defines itself as the nexus for artists of African descent locally, nationally, and internationally.[4] Locally, the museum has built partnerships and engaged artists in order to demystify and make accessible the processes of making and displaying contemporary art. Nationally, the museum has driven change in the cultural sector; without it employees of art museums in the United States would be even more homogenous than they are at present. Internationally, the Studio Museum occupies an essential position in constructing the narrative of contemporary African American and African Diaspora art. The findings for this case study were developed through a two-day site visit, which involved interviewing eight people, participating in an operations meeting, exploring galleries, and attending public programs.

Redefining Diversity: With a majority African American staff, the Studio Museum is an outlier among American museums. But, rather than dismissing diversity concerns as a non-issue, leaders and staff at the museum have developed a more nuanced view of the term.

Building Partnerships: As it prepares for a transitional period while a new facility is constructed, the Studio Museum sees community partnerships as a way to strengthen its relationship to Harlem.

Cultivating Artists and Curators: The Studio Museum in Harlem is, first and foremost, a space for cultivating talent. Between the Artist in Residence program and the networks established through director Thelma Golden, the Studio Museum in Harlem is an engine for cultivating and disseminating African American and African Diaspora art. This is primarily achieved through investing in artists and museum professionals.

History and Context

The mere existence of culturally specific spaces has confused and even provoked some stakeholders in the public sphere. For instance, Congressional Representative Jim Moran (D-Virginia) expressed concern in 2011 over the construction of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) in Washington DC, speculating during a federal appropriations hearing on Capitol Hill that culturally specific museums splinter an otherwise coherent national narrative along ethnic lines, and expressing fears that an investment in culturally specific spaces would isolate ethnic groups: “The Museum of American History is where all the white folks are going to go, and the American Indian Museum is where Indians are going to feel at home. And African Americans are going to go to their own museum. And Latinos are going to go to their own museum. And that’s not what America is all about.”[5] Such remarks invite an inspection of how culturally specific museums have developed and the purposes they serve, in order to better understand the contributions spaces such as the Studio Museum in Harlem make to their local, national and international audiences.

Edward M. Luby, director of the museum studies program at San Francisco State University, says that culturally specific museums, “Developed because the point of view reflected by traditional museums was perceived as excluding the experiences of certain cultural and ethnic groups […] places where objects associated with the histories of these groups were not being collected, and where the broad or specific stories of these groups were not being told through exhibits.”[6] The desire to create museums that collected the art of culturally specific groups, however, was not the only impetus behind their founding. In the late 1960s, when Museo del Barrio and the Studio Museum in Harlem were established in New York City, they were also designed as welcoming spaces for non-white audiences.

Harlem experienced dramatic demographic change at the start of the 20th century. In 1910 the neighborhood was ten percent African American. By 1930, it had grown to 70 percent African American, as Harlem became a primary destination for African Americans fleeing the Jim Crow south during the Great Migration. During this period the Harlem Renaissance emerged as an artistic and cultural movement in literature, music, and the visual arts, transforming the landscape of 20th century American art. As the significance of this movement has become an essential component of American culture, Harlem has become a national and international destination to engage with art of the African diaspora.

A collaborative effort among artists, philanthropists, and social workers brought the Studio Museum into existence in the 1960s, during a period of social unrest. Central to this collaboration was the social activism organization Harlem Youth Opportunities Unlimited (HARYOU).[7] Formed in 1962 as a community organization aiming to combat poverty and disenfranchisement in Harlem, HARYOU engaged Harlem youth in a number of different ways, not least of which was through the arts. Co-founder Dr. Kenneth Marshall says of the role of the arts in the community: “At HARYOU we say we are interested not in art for its own sake but art as equipment for living. We see art as an integral component.”[8]

Prior to the Studio Museum’s inauguration, co-founder Betty Blayton was working with Harlem youth at HARYOU. An artist herself, she was eager to see the students engaging with New York City’s cultural resources, and arranged for them to go to the Museum of Modern Art on the south end of Central Park–a few subway stops away. She quickly learned the students were being denied entrance to the museum by security. Blayton brought this to the attention of friend and curator, the poet Frank O’Hara, who helped to ensure that the students could access the museum.[9]

Recognizing the profound barriers that existed between MoMA and its potential Harlem audience, MoMA Junior Council member Frank Donnelly worked with Blayton to develop a cultural space in Harlem, eventually introducing other members of MoMA’s junior council to the project.[10] Over the next few years this initial collaboration between Donnelly and Blayton would grow into the Studio Museum in Harlem, named for its artist in residence program, which is still central to the museum’s mission.

Over the years the museum has grown into a premier international site for African American and African diaspora art, significantly contributing to the prominence of black artists such as Romare Bearden, Jacob Lawrence, Betye Saar, Lorna Simpson, Kara Walker, Kerry James Marshall, and many others. Public program and curatorial staff described a degree of freedom black artists experience in the museum, explaining that they don’t have to fight for their space, or have their work defined through a racial lens, as is sometimes the case in mainstream museums that display art from underrepresented groups in a tokenistic way.

Redefining Diversity

Considerations of diversity through the lens of the Studio Museum challenge familiar conceptions of the term. In part, this is because the museum has persisted through multiple cycles of these national conversations—the “war on poverty” in the 1960s, multiculturalism in the 1990s, the present focus on inclusion and equity as integral concepts to consider alongside representational diversity. The institutional memory of these phases creates a measured approach to the heightened public discourse surrounding identity politics in the arts and entertainment sectors. As Golden put it, “I opted out of the diversity conversation and really just got to work.”

Given the notable lack of African American employees in the broader museum sector, the Studio Museum offers a strong counterweight, acting as a source of diversity, indeed an engine for diversity, for the art museum community as a whole. Without the Studio Museum and a few similar museums around the country, the sector would face an even greater gap.

“For us, diversity of the institution also means the diversity of Harlem and its changing nature. It’s not just a black-white switch. It’s equally about cross-cultural diversity.”

When we asked staff about the museum’s relationship to diversity a host of complexities arose. At the Studio Museum, binary approaches to diversity lose their centrality. The census’s monolithic category “Black or African American” becomes too broad, failing to account for differences in regional and national origin, for instance. The binary approach to issues of diversity—focusing on white non-Hispanic versus people of color—is appropriately blunt at the national level, where aggregate statistics provide evidence of systemic barriers for people of color to enter and advance in the cultural sector. But at the Studio Museum, considerations of diversity do not disappear when those barriers are removed. Rather, they become more nuanced. As Golden put it: “For us, diversity of the institution also means the diversity of Harlem and its changing nature. It’s not just a black-white switch. It’s equally about cross-cultural diversity. I am deeply interested in a range of issues, such as age, positionality, well beyond race.”

With respect to the complexity of the museum’s approach to diversity, there was a high level of alignment among staff. Interviewees echoed Golden’s emphasis on age as an important element of diversity, especially in audience development, but also in some cases relevant to staff. Shannon Ali, director of visitor services, underscored the importance of focusing not just on developing a primarily youth audience—an issue she saw as all too pervasive in the broader museum sector—but also bringing into the museum the wealth of experience of a more senior audience.

In other interviews, the boundaries broadened further. Sheila McDaniel, deputy director of finance and operations, drew from her experiences in the corporate sector when describing the value of sustaining a diversity of ideas in an institution, as opposed to physical identity. “Part of this discussion,” she said, “is about failures of the multicultural moment. We can learn from the 70s and 80s. Corporations were essentially stating, ‘we just need your skin color and sexual parts,’ but then turn you into corporate drones.” McDaniel emphasized that a diversity of ideas is necessary to allow institutions to thrive, rather than erasing the individual’s perspective.

Two white staff members spoke to the sense of inclusion at the Studio Museum. Echoing McDaniel’s point, registrar Gina Guddemi, compared Studio to a previous work environment that was “more corporate,” noting that Studio Museum felt younger and more innovative. She described the diversity at the museum as “amazing,” viewing it as an important factor for the museum’s climate. Associate curator Hallie Ringle expressed similar sentiments, emphasizing that in working at the Studio, her notion of diversity had broadened. This is the only museum considered in this study where white employees were in the minority, and the Studio Museum’s practice of inclusion appears to encourage a commitment to the museum’s mission. “This institution has now become a place for someone who is not a person of color to learn about our subject,” Golden says. “It’s not only the job of diverse staff to produce diverse programming.”

These findings point to an opportunity for museums to deepen practices of inclusion as they grow more diverse. “Diversity” is not an agenda item that can be crossed out after some arbitrary threshold is passed. Were systemic barriers to advancement for people of color in the cultural sector removed, we would have a greater opportunity to think about diversity in a more nuanced way.

Building Partnerships

From its inception, the question of who the Studio Museum serves has been complex. Initially conceptualized as a space for integration, where the black and white art worlds could meet, the critiques of self-serving politicians and “white slumming” led to a shift in leadership and mission.[11] In 1968 the museum became exclusively concerned with representing African American art. That mission has since expanded to include art of Africa and the African diaspora.

The reach of the museum has also shifted significantly as it has grown. In the 1960s it was established in response to local issues, even if those issues were indicative of national struggles and connected to federal initiatives related to the “war on poverty.” In the final decades of the twentieth century, Harlem gentrified. It increasingly became an international tourist destination, and the Studio Museum along with it.[12] Now the museum is firmly established as a destination for international visitors.

As its reach has expanded, the museum finds itself wanting to recapture some parts of its local focus, reconnecting to its place in Harlem and its local audience and community.

But as its reach has expanded, the museum finds itself wanting to recapture some parts of its local focus, reconnecting to its place in Harlem and its local audience and community. One major reason for this return to Harlem is that the museum will be without a physical building, starting in 2018, for at least two years. The new construction will increase the limited gallery space, update the offices, and improve the HVAC system. In order to maintain its local presence without a physical building, the Studio Museum will have to engage in partnerships with local organizations and local spaces.[13]

To this end, a new program called inHarlem seeks to build these connections in the community. Partnering with the New York City Parks Department and New York Public Library, inHarlem started in 2016 as a set of initiatives meant to expand the Studio Museum’s presence outside the museum’s walls. This initiative creates an opportunity for site specific public art in neighborhood parks and builds collaborative partnerships, which create multiple entry points to the museum. One such event, Studio Salon, a partnership with the George Bruce Library, has created an opportunity to explore intersections between creative writing and contemporary art.[14]

Studio Salon recently launched Kellie Jones’s book, South of Pico, which was developed from her popular 2015 exhibition featuring under-recognized Los Angeles-based black artists called Now Dig This! Jones, associate professor of art history and director of undergraduate studies at Columbia University, led a conversation with MoMA research consortium fellow Ashley James and Los Angeles-based artist Sadie Barnett that explored both the content and method of Jones’s work. Jones’s book required intense archival research, highlighting the extreme lengths often necessary to uncover these forgotten narratives. South of Pico offers an important revision to the art historical narrative of 20th century American art.[15] Releasing the book at the Museum during the transition to inHarlem programming created a public space for this expansion of the canon.

While the Studio Salon creates a point of connection between writing and the visual arts, much of the museum’s educational programming connects artists with the public, demystifying the process of making visual art and encouraging the museum’s audiences to pursue creative outlets. In this sense, the museum carries on HARYOU-ACT’s mission of integrating the arts into the lives of Harlem residents.

For instance, Studio Squared, more informally known as “drink and draw,” offers hands-on art making workshops for adults. In many cases an artist affiliated with the Studio Museum will talk through their process and give the attendees a chance to create an art object using a similar method. Nico Wheadon, director of public programming, noted that this is one of the most popular programs, driven primarily by the informality of it: “It appeals to people who are exhausted by the institution they came from. They don’t want any theory, they want to meet people, learn something, and build something.”

In another program, Expanding The Walls (ETW), youth train with an artist, using Harlem as their subject matter, to learn the basics of photography. Inspired by the famous Harlem Renaissance photographer James Van Der Zee, the program concludes with an exhibition of his work alongside the students.

These programs speak to the museum’s efforts to strengthen ties with its local community. Through these and other local pursuits, the museum has prepared to deepen its connection to Harlem while it is without a physical space and is prepping for a new level of engagement once its new space is completed.

Cultivating Artists and Curators

Creating opportunities for audiences and artists to come together is only natural for a museum which is named for its artist residency program. The Artist in Residence (AIR) studios are above the galleries, and the work produced during the residency eventually finds its way into the museum’s permanent collection—the museum typically purchases one of the pieces resulting from the residency. One current artist in residence, Andy Robert, described the significance of the residency: “Studio Museum has a lot more visibility and community/public engagement [than other residencies]. Even though it’s private, there’s a sense that, because of how competitive it is, the residents are seen.” He described the value that comes from Golden’s reputation. In addition to financial support, providing a studio space and a thriving creative environment, the residency serves as an access point for emerging artists to New York galleries. In this way, the museum is responsible for launching dozens of careers for emerging artists.

The Studio Museum has played a critical role as an incubator for curators, a function Golden actively cultivates. To highlight just a few former Studio Museum curators and staff since 2010 who have since progressed to other museums:

- Naomi Beckwith is now a curator at MCA Chicago

- Christine Y. Kim is now a curator at LACMA

- Lauren Haynes is now contemporary curator at Crystal Bridges, and in the upcoming class for the Center for Curatorial Leadership

- Thomas Lax is an associate curator at MoMA

- Naima Keith is Deputy Director at the California African American Museum

- Sandra Jackson-Dumont is Frederick P. and Sandra P. Rose Chairman of Education at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Rujeko Hockley is Assistant Curator at the Whitney Museum

These matriculations reflect just a fraction of Studio Museum’s influence on the staffing of arts administrators of color in the broader field.

Golden also works to cultivate a selection of curators through professional development initiatives. This year the Studio Museum brought ten curators at varying stages of their careers and from a number of different museums around the country on a traveling curatorial development program aimed at fostering cross cultural dialogue. All of the curators had intellectual investments in artists of African descent, locally, nationally, and internationally, aligning with the Studio Museum’s mission. The program itinerary included two destinations, selected for unique exhibition opportunities. Participants first visited London to attend the opening of Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power at the Tate Modern. The exhibition brought a heightened awareness to the cultural heritage of African Americans to a British audience through the works of Betty Saar, Melvin Edwards, Barclay Hendricks, Norman Lewis, and Noah Purifoy, among others.

Following the Tate, the cohort attended the Venice Biennale, where Mark Bradford represented the United States with his exhibition Tomorrow is Another Day. Bradford was the fourth person of color to represent the United States since the Biennale was established 120 years ago.

On this trip, curators traveled with Studio Museum donors and had the opportunity to visit the private collections of philanthropists and attend cultivation events. In this way, participants gained insight and experience that is often out of reach for emerging professionals.

As a training ground for curators, a springboard for artists, and a leader in constructing the narrative of African American and African Diaspora art, the Studio Museum has been effective in illuminating the local national and international cultural contributions of black artists to the broader art world and public.

As a training ground for curators, a springboard for artists, and a leader in constructing the narrative of African American and African Diaspora art, the Studio Museum has been effective in illuminating the local national and international cultural contributions of black artists to the broader art world and public. Golden sees these contributions manifesting through shifts in art history programs. Over the last 30 years the academic trends have shifted away from relegating African American art to a subcategory of American art. As she described, “Now there are many departments offering standalone art history courses [in African American and African diaspora art] – and that affects my intern pool. It’s broader. Young people of all ethnicities and races. And then they will go ahead and get a Master’s or PhD. There’s a wider group of people who are self-selecting into the pool.”

While a critique of culturally specific museums is that they create cultural divisions, this development reveals the museum as a force of integration in several respects. It has served as an entry point for many people of color to professional positions in the arts. And it has also been effective in bringing African American and African Diaspora art to a broader public. The uptick in art history courses focusing on this subject matter is evidence that the spectrum of curators and administrators qualified to present African American and African Diaspora art in thoughtful ways is growing.

Conclusion

The Studio Museum has had an undeniable impact in diversifying the staff of cultural organizations and raising awareness around African American and African diaspora art historical narratives in the sector. While difficult to quantify, this impact is felt across many other museums as well. Golden’s success in increasing staff and program diversity relies on a philosophy that is easily universalized: do what you can. She has positioned herself and the Studio Museum to act as an engine for diversity in the sector.

Now, while others become aware of the importance of these efforts, she shifts her attention to the experiences of those she has shepherded into various museums and cultural organizations: “You’re interested in why there aren’t more people in this field,” she told us. “I’m really most interested in the lives of the people in these positions.”

Perhaps the most resounding lesson from the Studio Museum was that the work of building an inclusive, diverse and equitable institution and community is never over. While national attention to these issues functions in cycles, there is value in the persistence of organizations that make these values integral to their daily operations, regardless of the current public discourse.

Appendix

Case Studies in Inclusion, Diversity, and Equity among AAMD Member Art Museums

Three years ago, Ithaka S+R, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD), and the American Alliance of Museums (AAM) set out to quantify with demographic data an issue that has been of increasing concern within and beyond the arts community: the lack of representative diversity in professional museum roles. Our analysis found there were structural barriers to entry in these positions for people of color. After collecting demographic data from 77 percent of AAMD member museums and an additional cohort of AAM art museums that are not members of AAMD, we published a report sharing the aggregate findings with the public. In her foreword to the report, Mariët Westermann, executive vice president for programs and research at the Mellon Foundation, noted, “Non-Hispanic white staff continue to dominate the job categories most closely associated with the intellectual and educational mission of museums, including those of curators, conservators, educators, and leadership.”[16] While museum staff overall were 71 percent white non-Hispanic, we found that many staff of color were employed in security and facilities positions across the sector. In contrast, 84 percent of the intellectual leadership positions were held by white non-Hispanic staff. Westermann observed that “these proportions do not come close to representing the diversity of the American population.”

The survey provided a baseline of data from which change can be measured over time. It has also provoked further investigation into the challenges of demographic representation in this sector. Many institutional leaders are growing increasingly aware of demographic trends showing that in roughly a quarter century, white non-Hispanics will no longer be the majority in the United States, whereas ten years ago the white non-Hispanic population was double that of people of color.[17] This rapid growth indicates that cultural institutions such as museums will need to be intentional and strategic in order to be inclusive and serve the entire American public.

To aid these efforts, AAMD, the Mellon Foundation, and Ithaka S+R partnered again to launch a new effort to understand the following: What practices are effective in making the American art museum more inclusive? By what measures? How have museums been successful in diversifying their professional staff? What do leaders on issues of social justice, equity, and inclusion in the art museum have to share with their peers?

Using the data from the 2015 survey, we identified 20 museums where underrepresented racial/ethnic minorities have a relatively substantial presence in the following positions: educators, curators, conservators, and museum leadership. We then gauged the interest of these 20 museums in participating, also asking a few questions about their history with diversity. In shaping the final list of participants, we also sought to ensure some amount of breadth in terms of location, museum size, and museum type. Our final group includes the following museums:

- The Andy Warhol Museum (Pittsburgh)

- Brooklyn Museum

- Contemporary Arts Museum Houston

- Detroit Institute of Arts

- Los Angeles County Museum of Art

- Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago

- Spelman College Museum (Atlanta)

- Studio Museum in Harlem.[18]

In shaping the final list of museums to profile, we also sought to ensure some amount of breadth in terms of location, size, and type.

We then conducted site visits to the various museums, interviewing between ten and fifteen staff members across departments, including the director. In some cases, we also interviewed board members, artists, and external partners. We observed meetings, attended public events, and conducted outside research.

In the case studies in the series, we have endeavored to maintain an inclusive approach when reporting findings. For this reason, we sought the perspectives of individual employees across various levels of seniority in the museum. When relevant we have addressed issues of geography, history, and architecture to elucidate the museum’s role in its environment. In this way the museum emerges as a collection of people—staff, artists, donors, public. This research framework positions the institution as a series of relationships between these various constituencies.

We hope that by providing insight into the operations, strategies, and climates of these museums, the case studies will help leaders in the field approach inclusion, diversity, and equity issues with a fresh perspective.

Endnotes

- Please see the Appendix at the end of this paper for a fuller description of the survey, methodology, and how we selected museums to include in this case study series. ↑

- Roger Schonfeld, Mariët Westermann, and Liam Sweeney, “Art Museum Staff Demographic Survey,” The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, July 29, 2015, https://mellon.org/media/filer_public/ba/99/ba99e53a-48d5-4038-80e1-66f9ba1c020e/awmf_museum_diversity_report_aamd_7-28-15.pdf. ↑

- This project benefitted greatly from the contributions of the advisory committee. Our thanks to Johnnetta Betsch Cole, Senior Consulting Fellow at the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation; Brian Ferriso, Director of Portland Art Museum; Jeff Fleming, Director of Des Moines Art Center; Lori Fogarty, Director of Oakland Museum of California; Alison Gilchrest, Program Officer, The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation; Susan Taylor, Director of New Orleans Museum of Art; and Mariët Westermann, Executive Vice President, The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.We would also like to thank Christine Anagnos, Executive Director AAMD, and Alison Wade, Chief Administrator AAMD, for their organizational support in this project.And we are grateful to Thelma Golden, Director of the Studio Museum in Harlem for her willingness to participate in the study, and Evans Richardson, chief of staff, for his many contributions to the project. ↑

- The museum’s full mission statement: “The Studio Museum in Harlem is the nexus for artists of African descent locally, nationally and internationally and for work that has been inspired and influenced by black culture. It is a site for the dynamic exchange of ideas about art and society.” ↑

- Robyn Autry, “MEMORY DEVIANTS: Breaking the Collective,” In Desegregating the Past: The Public Life of Memory in the United States and South Africa, 145-85, NEW YORK: Columbia University Press, 2017, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7312/autr17758.10. ↑

- Edward M. Luby, “How Ethnic Museums Came About,” The New York Times, April 26, 2011, accessed September 07, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2011/04/26/should-we-have-a-national-latino-museum/how-ethnic-museums-came-about. ↑

- It would later combine with Associated Community Teams and be known as HARYOU-ACT ↑

- “Interview with Kenneth Marshall, Program Director of HARYOU-ACT,” WNYC, accessed September 06, 2017, http://www.wnyc.org/story/interview-with-kenneth-marshall-program-director-of-haryouact/. ↑

- Susan Cahan, Mounting Frustration: The Art Museum in the Age of Black Power (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016). ↑

- MoMA’s junior council was formed in 1949 to cultivate young potential donors. ↑

- Susan Cahan, Mounting Frustration: The Art Museum in the Age of Black Power (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016). ↑

- Thomas J. Lueck, The New York Times, April 17, 1988, accessed August 7, 2017, http://www.nytimes.com/1988/04/17/weekinreview/the-region-japanese-interest-in-harlem-megaprojects-create-hope-and-fear.html. ↑

- Robin Pogrebin, “Studio Museum in Harlem Unveils Design for Expansion,” The New York Times, July 05, 2015, accessed August 08, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/06/arts/design/studio-museum-in-harlem-unveils-design-for-expansion.html?_r=0. ↑

- Studio Salon preceded the inHarlem initiative, and is now part of a partnership with NYPL. ↑

- Firelei Baez, one of the artists on display in the Studio Museum’s exhibition Regarding the Figure (2017), said of Jones’s work: “There are so many artists who wouldn’t be part of the conversation without her work. She’s actively sought out artists who were missed by a lot of exhibitions. Without her you wouldn’t know about them. Kellie Jones redefined African American art history. Art within diaspora is usually a minor strand of bigger fabric, she is making us see it’s crucial. My work wouldn’t exist in the way that it does without her.” ↑

- Roger Schonfeld, Mariët Westermann, and Liam Sweeney, “Art Museum Staff Demographic Survey,” Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, July 29, 2015, https://mellon.org/media/filer_public/ba/99/ba99e53a-48d5-4038-80e1-66f9ba1c020e/awmf_museum_diversity_report_aamd_7-28-15.pdf. ↑

- William H. Frey, “A Pivotal Period for Race in America,” In Diversity Explosion: How New Racial Demographics Are Remaking America (Washington DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2015), 1–20, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7864/j.ctt6wpc40.4. ↑

- We focused on people of color for measuring diversity for two reasons: (1) In the 2015 art museum demographic study, we received substantive data for the race/ethnicity variable, unlike other measures such as LGBTQ+ and disability status, which are not typically captured by human resources, and (2) in the study we found ethnic and racial identification to be the variable for which the degree of homogeneity was related to the “intellectual leadership” aspect of the position (i.e., curator, conservator, educator, director). We are alert to issues of accessibility in this project, and although it was not foregrounded in our original project plan we hope to address these questions in more depth in future projects. ↑

Attribution/NonCommercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of the license, please see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.